Or, Why Edgar Allan Poe, a Few Other Dead Guys, and My Irish Relatives Kinda Knew What They Were Doing with All Those Words (Mostly)

Alright, so, it’s Thursday afternoon. Just after 1:30. I’m lookin’ out the window here in Somewhere, USA, and it’s probably, I don’t know, historic out there. People are probably re-enacting something. Meanwhile, I’m supposed to talk about… uh…learning grammar. Yeah, through literature.

Yeah. My dad would have just called it “reading a book.” But okay, “Learning Grammar Through Literature.” Sounds like something you’d sign up for if your other option was, like, cleaning grout with a toothbrush.

The idea, apparently, is that instead of just memorizing rules like “i before e except after c, unless it sounds like ‘a’ as in neighbor and weigh, and on weekends and holidays and whenever the hell else it decides to change its mind,” you can just read famous dead guys and somehow absorb grammar. Like osmosis, but with more semicolons.

So, let’s look at some of these literary heavy hitters and how they supposedly teach you not to sound like a moron.

First up, Edgar Allan Poe. “The Tell-Tale Heart.” Right, the dude with the beating floorboard. Apparently, Eddie was a whiz with syntax. That’s just a fancy word for how you put your sentences together. He uses these short, choppy sentences – like when you’re trying to tell a story but you’re also pretty sure the cops are listening. You know: “True!—nervous—very, very dreadfully nervous I had been and am; but why will you say that I am mad?” See all those dashes? That’s not bad typing; that’s strategic. It’s like he’s out of breath, or maybe just out of his mind. So, by reading Poe, you see how punctuation isn’t just little speckles on the page; it’s like the gas pedal and the brake for the story’s mood. Good to know, I guess, if you’re planning on writing a story about a crazy person. Which, let’s be honest, is most writers.

Next, Mark Twain. “A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court.” Now, Twain, he liked to have his characters talk like actual people. Or, you know, actual people from a hundred years ago. Which means they weren’t always using their “King’s English,” if you know what I mean. Lots of slang, dialects, words that’d make your English teacher’s eye twitch. But it worked. It made the characters sound real, gave ’em personality. So, you read Twain, and you learn that sometimes breaking the grammar rules makes things funnier or more authentic. It’s like, my Irish relatives, their grammar is… creative. But you know exactly what they mean, and it’s usually hilarious. So, thanks, Mark. Permission to not always sound like a robot.

Next, Mark Twain. “A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court.” Now, Twain, he liked to have his characters talk like actual people. Or, you know, actual people from a hundred years ago. Which means they weren’t always using their “King’s English,” if you know what I mean. Lots of slang, dialects, words that’d make your English teacher’s eye twitch. But it worked. It made the characters sound real, gave ’em personality. So, you read Twain, and you learn that sometimes breaking the grammar rules makes things funnier or more authentic. It’s like, my Irish relatives, their grammar is… creative. But you know exactly what they mean, and it’s usually hilarious. So, thanks, Mark. Permission to not always sound like a robot.

Can’t talk about literature without Shakespeare. “King Lear.” Billy Shakes, master of everything, apparently, including making your brain hurt with words you’ve never heard of. He mixes up poetry and regular talking, short sentences, long sentences. And he bent grammar rules like they owed him money. “How sharper than a serpent’s tooth it is to have a thankless child!” Try diagramming that sentence after a couple of beers. He’s showing you that word order, rhythm, and all that fancy “figurative language” can pack a bigger punch than just saying “It stinks when your kids are brats.” So, yeah, Shakespeare: good for drama, also good for making you realize grammar can be a bit of a free-for-all if you’re famous enough.

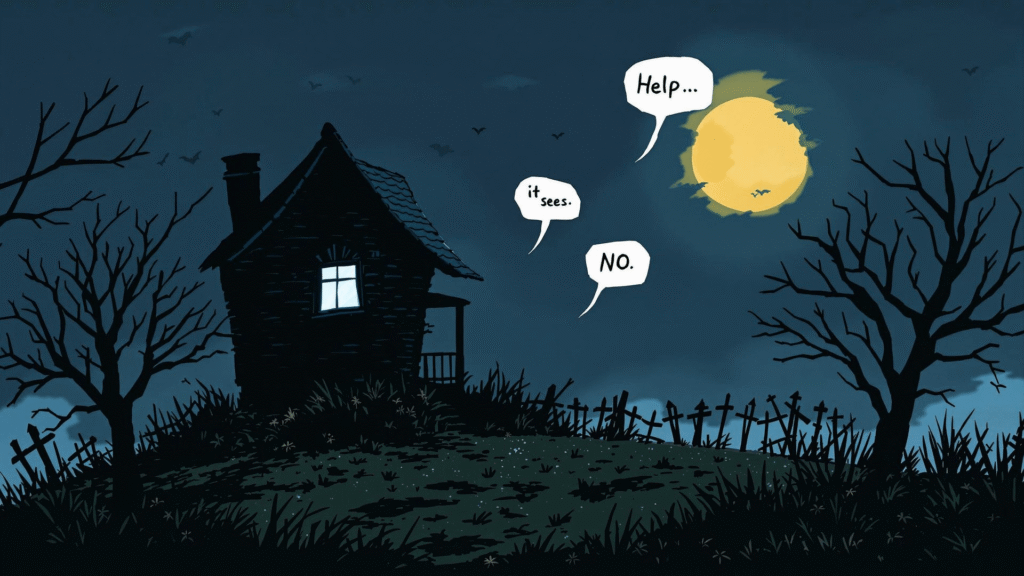

Last on this hit parade, Shirley Jackson. “The Haunting of Hill House.” Spooky stuff. And Shirley, she knew how to use short, stabby sentences to make you uneasy. Like: “It was a house that had a reputation. It was not a good reputation.” Boom. Boom. No messing around. Simple, direct, makes the hair on your arms stand up a little. So, from her, you learn that sometimes saying less, with simple grammar, says a whole lot more. Especially if you’re trying to creep people out.

So, the big takeaway from all these literary gymnastics? Reading these folks, with their fancy sentences and rule-bending, can supposedly make you better at grammar. Because you see it in action, not just as a list of “don’ts” from your seventh-grade teacher, Mrs. McGillicuddy, who probably smelled like mothballs and despair.

They say each author’s style shows different “grammatical principles” and the “artistry behind language”. Okay, sure. I guess it’s like learning to cook by eating at fancy restaurants instead of just reading the ingredients list on a box of mac and cheese.

So, go ahead. “Embrace your literary exploration and unlock the wonders of grammar.” Or, you know, just read a good story and try not to end your sentences with a preposition unless you absolutely have to. Whatever works. Now, if you’ll excuse me, all this talk of syntax and clauses, I think I need a beer. Or maybe just a nap.